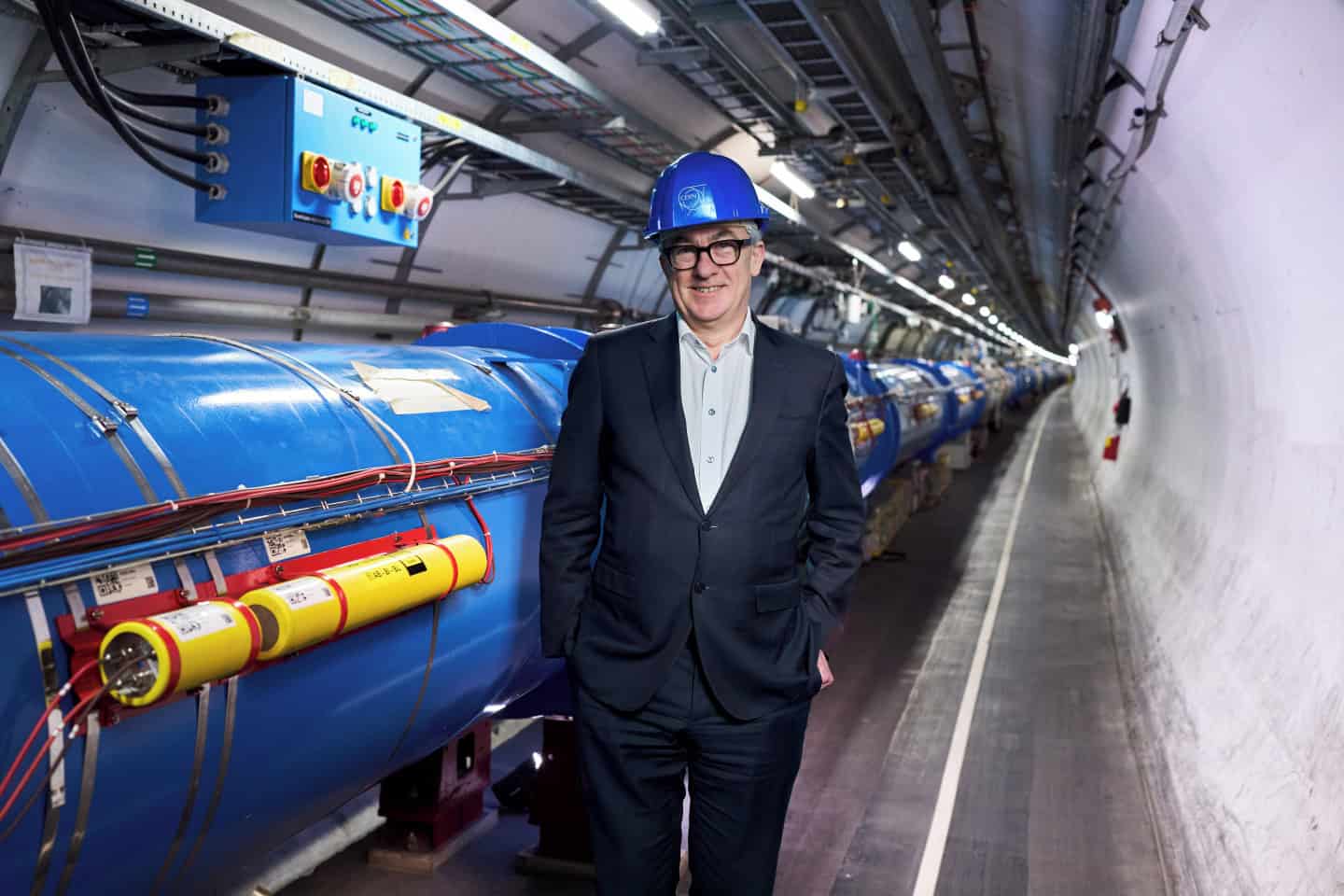

Incoming CERN Director-General Mark Thomson Outlines His Future Priorities

Mark Thomson, who will take over from Fabiola Gianotti as director-general of CERN next year, talks about his plans in the hot seat and the challenges ahead for high-energy physics. Interview originally published in Physics World.

Mark Thomson, who will take over from Fabiola Gianotti as director-general of CERN next year, talks about his plans in the hot seat and the challenges ahead for high-energy physics. Interview originally published in Physics World.

How did you get interested in particle physics?

I studied physics at the University of Oxford and was the first person in my family to go to university. I then completed a DPhil at Oxford in 1991, studying cosmic rays and neutrinos. In 1992, I moved to University College London as a research fellow. That was the first time I went to CERN, and two years later, I began working on the Large Electron-Positron Collider, the predecessor of the Large Hadron Collider. I was fortunate enough to work on some of the major measurements of the W and Z bosons and electroweak unification, so it was a great time in my life. In 2000, I worked at the University of Cambridge, where I set up a neutrino group. It was then that I began working at Fermilab, the U.S.’s premier particle physics lab.

So you flipped from collider physics to neutrino physics?

Over the past 20 years, I have oscillated between them and sometimes done both in parallel. Probably the biggest step forward was in 2013 when I became spokesperson for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment—a fascinating, challenging, and ambitious project. In 2018, I was appointed executive chair of the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), one of the main UK funding agencies. The STFC funds particle physics and astronomy in the UK, maintains relationships with organizations such as CERN and the Square Kilometre Array Observatory, and operates some of the UK’s biggest national infrastructures, including the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and the Daresbury Laboratory.

What did that role involve?

It covered strategic funding of particle physics and astronomy in the UK and involved running a large scientific organization with about 2,800 scientific, technical, and engineering staff. It was very good preparation for the role of CERN director-general.

What attracted you to become CERN director-general?

CERN is such an important part of the global particle-physics landscape. But I don’t think there was ever a moment where I just thought, "Oh, I must do this." I’ve spent six years on the CERN Council, so I know the organization well. I realized I had all the tools to do the job—a combination of the science, knowledge of the organization, and my experience in previous roles. CERN has been a large part of my life for many years, so it’s a fantastic opportunity for me.

What were your first thoughts when you heard you had got the role?

It was quite a surreal moment. My first thoughts were, "Well, OK, that’s fun," so it didn’t really sink in until the evening. I’m obviously very happy, and it was fantastic news, but it was almost a feeling of, "What happens now?"

What happens now as CERN director-general designate?

There will be a little bit of shadowing, but you can’t shadow someone for the whole year—that doesn’t make much sense. So I really have to understand the organization, how it works from the inside, and, of course, get to know the fantastic CERN staff, which I’ve already started doing. A lot of my time at the moment is spent meeting people and understanding how things work.

How might you do things differently?

I don’t think I will do anything too radical. I will look at where we can make things work better. But my priority for now is putting in place the team that will work with me from January. That’s quite a big chunk of work.

What do you think your leadership style will be?

I like to put around me a strong leadership team, then delegate and trust them to deliver. I’m there to set the strategic direction but also to empower them. That means I can take an outward focus and engage with the member states to promote CERN. I aim to create a culture where staff can thrive and operate in a very open and transparent way. That’s very important to me because it builds trust both within the organization and with CERN’s partners. I’m also 100% behind CERN being an inclusive organization.

So diversity is an important aspect for you?

I am deeply committed to diversity, and CERN is committed to it in all its forms. This is a common value across Europe—our member states see diversity as critical, and it matters to our scientific communities. If we’re not supporting diversity, we’re losing people who are no different from others who come from more privileged backgrounds. At CERN, diversity also means national diversity. CERN is a community of 24 member states and several associate member states, and ensuring nations are represented is incredibly important. It’s how you do the best science, ultimately, and it’s the right thing to do.

The LHC is undergoing a £1bn upgrade towards a High Luminosity-LHC (HL-LHC). What will that entail?

The HL-LHC is a big step up in terms of capability, with the goal of increasing the luminosity of the machine. We are also upgrading the detectors to make them even more precise. The HL-LHC will run from about 2030 to the early 2040s. By the end of LHC operations, we would have only taken about 10% of the overall data set once you add what the HL-LHC is expected to produce.

What physics will that allow?

There’s a very specific measurement we would like to make around the nature of the Higgs mechanism. The Higgs boson has a very strange vacuum potential—it’s always there in the vacuum. With the HL-LHC, we’re going to start to study the structure of that potential. That’s a really exciting and fundamental measurement, and it’s where we might start to see new physics.

Beyond the HL-LHC, you will also be involved in planning what comes next. What are the options?

We have a decision to make on what comes after the HL-LHC in the mid-2040s. It seems far off, but these projects need a 20-year lead-in. The consensus among the scientific community has been that the next machine must explore the Higgs boson. The motivation for a Higgs factory is incredibly strong.

Yet there has not been much consensus on whether that should be a linear or circular machine?

My personal view is that a circular collider is the way forward. One option is the Future Circular Collider (FCC), a 91 km circumference collider that would be built at CERN.

What would the benefits of the FCC be?

We know how to build circular colliders, and they offer significantly more capability than linear machines by producing more Higgs bosons. It is also a research infrastructure that will remain for many years beyond the electron-positron collider. At some point in the future, we will need a high-energy hadron collider to explore the unknown.

But it won’t come cheap, with estimates being about £12–15bn for the electron–positron version, dubbed FCC-ee?

While the price tag is significant, it is spread over 24 member states for 15 years, and contributions can also come from elsewhere. It will not be easy to secure that funding, as money will need to come from outside Europe as well.

China is also considering the Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC), which could be built by the 2030s. What would happen to the FCC if the CEPC were to go ahead?

That will be part of the European Strategy for Particle Physics, which will be discussed this year. Nothing has really been decided in China—it’s a big project and may not go ahead. CERN has the scientific and engineering heritage in building and operating colliders. There is only one CERN in the world.

What do you make of alternative technologies such as muon colliders?

It’s an interesting concept, but technically, we don’t yet know how to do it. A lot of development work is needed, and turning it into a real machine will take a long time. Looking at a muon collider for the mid-2040s is probably unrealistic. When the HL-LHC stops in 2040, there needs to be a clear next step.

Image: Looking ahead: Mark Thomson will take up the position as CERN director-general on 1 January 2026. Credit: CERN